Investing Part 4 – Portfolios

About 12 minutes (hang in there!)

Now that we’ve talked about investing basics, investing returns, and investing risk, it’s time to put these all together and talk about your investment portfolio.

But before we get started, just a quick reminder that this guide, like our others, is meant for educational purposes. We are not here to manage your money. We’re going to be talking about concepts and using examples, but they’re just that, examples. So it will be up to you, or your financial advisor, to determine the right portfolio for you. With that, on to portfolios!

Here’s what we cover

What is a portfolio

Keeping it simple to start

Your asset allocation

The 100 minus your age rule

Considering your personal situation

Adding a little more complexity

Putting it together (for stocks)

Adding bonds to the mix

Customizing your allocation

Monitoring and rebalancing

Sticking to your plan

First off, what is a portfolio anyway?

Your portfolio is just a fancy way of describing all of your investments combined.

So if you have some investments in a 401(k), some in an IRA, and some in a brokerage account, all of these would be considered part of your portfolio. Or if you don’t have any of these, that’s alright too! There’s no time like the present to get started.

You may also be wondering how your cash accounts (checking accounts, savings accounts, money market accounts) fit in. While we usually don’t refer to cash as an “investment” like stocks and bonds, it certainly is an asset, so we’re going to include it.

Keeping it simple to start

To understand how portfolios work, it’s helpful to start with a very simple portfolio – one made up of only two asset classes: stocks and bonds.

Actually, this really isn’t a huge stretch of the imagination. For many of us, our portfolios will be comprised mostly of stocks and bonds. But we’ll get to some slightly more nuanced scenarios shortly, so be patient.

As we discussed in Investing Risk, stocks and bonds each have their benefits and drawbacks.

Stocks tend to offer higher returns over time and do a better job of protecting your money against inflation (which is good). But they also carry more market risk, meaning they fluctuate in price more (which is not so good).

Bonds are basically the reverse. They generally have lower market risk (good), but tend to offer lower returns and have more inflation risk (not so good).

So by combining the two in a portfolio, we can utilize their benefits, while managing their drawbacks. Essentially, stocks can be used to grow your money for the long term, and bonds (and cash) can be used for stability and to meet nearer-term money needs.

How do you choose the right mix of each?

This is where your asset allocation comes in (one of those terms that sounds complicated but really isn’t). It actually just means the mixture of your investments.

For example, if half of your portfolio is invested in stocks, you would say your stock allocation is 50%. Not so tricky, right?

Alright, so how much should you allocate to each asset class?

Well, there are a number of ways you could do this – some better than others. If we’re just talking about investing in stocks and bonds, you might be tempted to put half of your money in stocks and the other half in bonds. In fact, this has a name in the world of behavioral finance: naive diversification. And research actually shows that people tend to do this in real life. When given several investment options, we often just split our money evenly across all of them.

But, as you can probably guess from the name (is “naive” ever a good thing?), this really isn’t a great approach. It doesn’t take into account anything specific about your situation or about the nature of the investments themselves.

So what should you actually do? Let’s dig some more.

The 100 minus your age rule

One of the main factors you’ll want to consider is your investment horizon, meaning how long you’ll be investing your money.

If you’re young and have several decades of investing ahead, you can typically handle more market risk and hold a higher proportion of stocks. You’ll be able to take advantage of their higher returns, and if stocks do take a nose dive, you’ll have more time to recover.

Then as you get older and closer to retirement, you’ll probably want to shift more of your portfolio to bonds and cash because of the stability they offer.

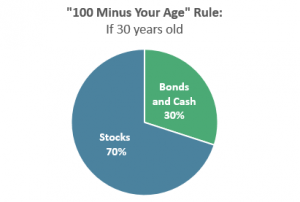

A frequently used rule of thumb that takes this into account is the appropriately named the “100 minus your age” rule.

How it works: Subtract your age from 100. The number you get is the percentage of your portfolio you would invest in stocks.

So if you’re 30 years old, this rule says you would want to have 70% of your portfolio invested in stocks (100 – 30 = 70). The rest of your portfolio would be invested in safer assets (lower market risk), like bonds and cash. Here’s how it would look in pie chart form for that 30-year old.

Alternatively, if you’re 60 years old, you would have 40% of your portfolio invested in stocks (100 – 60 = 40). The remainder would be invested in bonds and cash. Another pie chart.

Okay, like any rule of thumb, the 100 minus your age rule isn’t perfect. But it’s actually a decent starting point as we get out bearings, and also a good sanity check along the way. In other words, you don’t necessarily want to take it literally, but it’s good to keep in mind.

Also consider your personal situation

You’ll also want to take into account other factors that are unique to you, including any specific cash needs on the horizon, like making a down payment on a home.

Generally speaking, if you’re talking about money you’ll need in the next couple of years, you probably don’t want to have it invested in stocks since they can be volatile. Instead, you’re probably better off keeping that money in bonds or cash.

You can also take into account your personal risk tolerance, which means your willingness and ability to take on financial risk. This is partly related to your investment horizon – the younger you are, the more risk you can usually afford to take. But you may simply feel comfortable taking on more financial risk and therefore feel more confident about holding a higher percentage of stocks.

A word of warning though, thinking you can tolerate more risk is not the same thing as actually tolerating it. Stocks inevitably hit rough patches. They can fall 10%, 20%, 50%, or more. And it’s hard to truly know how you’ll react until it happens. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t invest, but we need to understand the risks going in. And it’s also why we should keep a long-term mindset when we invest in the stock market.

Adding (a little) more complexity

So far we’ve only be talking about dividing a portfolio into two broad asset classes; stocks and bonds. And while simple is great, we can actually add a little more diversification to our portfolio by subdividing these asset classes further.

So why don’t we! Let’s start with stocks.

Stocks – Size and Geography

Two common ways to subdivide stocks are by company size (like Apple vs. a small, young business) and by company geography (Ford (U.S.) vs Toyota (Japan)).

Company Size

There are a few different ways to measure the size of a company. But one of the main ways is by something called the market capitalization (or just market cap for short). This refers to the total value of the company and represents what you would theoretically have to pay if you wanted to own all of the company’s stock (think Gordon Gekko).

There are three basic categories that are commonly used:

• Large cap stocks: companies that have a market capitalization of $10 billion or more

• Mid cap stocks: companies that have a market capitalization of $2 billion to $10 billion

• Small cap stocks: companies that have a market capitalization less than $2 billion

Some financial firms might use slightly different cutoff points in their definitions of each category, but they should be roughly the same.

All three categories have slightly different risk and return characteristics, i.e. sometimes small cap stocks will do better than large caps and vice versa. So by having some of your money invested in each, your portfolio will be a little more diversified.

Company Geography

In addition to diversifying your stocks by size, you can also diversify by geography, meaning you can invest some of your money in US-based stocks and some in international stocks. And international stocks are often further divided into developed markets (basically Europe, Japan, Australia, and Canada) and emerging markets (the four largest of these being Brazil, Russia, India and China).

In some years, international stocks may outperform US stocks and in other years the opposite will be true. So you can diversify your portfolio by having some of each, similar to how you can diversify across company size.

Bonds (and Cash)

The portion of your portfolio allocated to bonds can also be broken down further into sub-categories. And there are a few different ways you could do this.

Maturity Date (length of the bond)

As the term of the bond gets shorter and shorter, it becomes more like holding cash. In fact, money market funds, which are generally considered “cash” are actually invested in short-term bonds – bonds that will repay the borrowed within months instead of years. Because they repay so quickly, there’s very little risk of not getting your money back. It’s common to think in terms of holding some long-term bonds and some short-term bonds, or cash.

Credit Risk

While bonds are usually considered safer investments than stocks, there’s still a chance the borrower doesn’t repay the borrowed money on time or at all. This is referred to as credit risk. Bonds typically fall into one of two categories with respect to credit risk:

• Investment grade: Less credit risk and lower returns

• High-yield (sometimes called junk bonds): More credit risk and higher returns

If you want to get a mix of each, you could have some of your money in a high grade bond fund and some in a high-yield bond fund.

Geography

In the same way you can invest in international stocks, you can also invest in international bonds. These could be issued by international governments or by international corporations.

Inflation Protection

Most bonds are exposed to inflation risk because the interest payments and the principal amount are fixed (based on the bond contract). So if inflation rises unexpectedly, the payments and principal will be worth less than what you thought. However, as we briefly mentioned in Investing Risk, you can invest in certain bonds called Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities, or TIPS. These are designed so that the principal amount will actually increase with inflation, which means they’ll better protect you from inflation risk.

Real Estate

Real estate is the fourth major asset class in addition to stocks, bonds, and cash. This means it’s worth considering as you build your portfolio.

If you own your home, it will most likely represent a large portion of your wealth already. So you may not feel the need to add more real estate to your portfolio.

But, if you don’t own your home or would like to add more real estate exposure to your portfolio, you may want to invest some money in something called a REIT, which stands for Real Estate Investment Trust. Don’t get hung up on the name though. REITs are more or less like publicly traded mutual funds or ETFs that invest in real estate assets instead of stocks or bonds, which you can buy through your brokerage account.

Putting it all together

Okay, we’ve covered a lot and all of this might seem a little complicated at first. But once you get the hang of it, it’s really not so bad (trust us).

At this point, you’re probably wondering how you actually invest in these sub-categories of stocks and bonds.

Well, fear not! Decades of marvelous innovations (accompanied by some not-so-marvelous ones) in consumer finance have actually made it pretty easy to do.

Once you set up your investment account, you’ll be able to choose mutual funds and ETFs that have been created to specifically invest in these categories.

For example, let’s say you put $10,000 in a brokerage account. You could invest some of your money in a large-cap U.S. stock fund, some in a mid-cap U.S. stock fund, and some in a small-cap U.S. stock fund. And then you could invest some in international stocks – split between an international developed market fund and an emerging market fund.

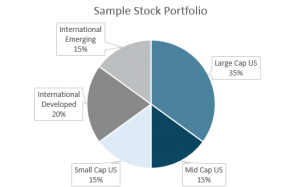

One possible breakdown (out of many) of the stock portion of your portfolio might look like this:

• 35%: U.S. Large Cap Stocks

• 15%: U.S. Mid Cap Stocks

• 15%: U.S. Small Cap Stocks

• 20%: International Developed Nation Stocks

• 15%: International Emerging Market Stocks

There are even some funds out there that are designed to have this level of diversification built in for you automatically so that you don’t need to own multiple ETFs or mutual funds. But owning a handful of funds is not that hard either. One of the great things about investing is that you have a lot of options that will work.

As always though, pay attention to the fees any particular fund charges.

Adding bonds and cash to our portfolio

But wait, that was just the stock portion of our hypothetical portfolio. So let’s say we now want to add some bonds and cash to the mix.

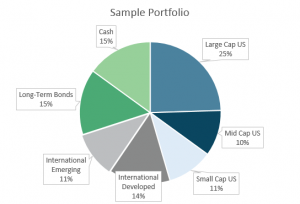

Let’s also assume we want to hold our overall portfolio weights at 70% invested in stocks and 30% invested in bonds and cash (100 minus age rule for a 30-year-old).

Here’s what it might look like

Notice that long-term bonds and cash represent 30% of the overall portfolio (15% each) and stocks represent 70% of the portfolio. So we’ve kept the overall stock vs bond & cash breakdown at 70/30. We’ve just sub-divided each into smaller sections of the pie.

Customizing your allocation

The sample allocations we’ve mentioned are really just meant for illustrative purposes. So you’ll want to figure out a portfolio allocation that’s right for you.

Maybe you want a more aggressive allocation focused on growing your portfolio. In that case, you would tilt your allocation toward stocks and other higher risk/higher return investments. Or maybe you want a more conservative allocation focused on protecting your wealth. Then you would tilt your allocation towards bonds and other more defensive investments.

The options are literally endless, but that doesn’t mean it needs to get overly complicated. As you continue learning more about personal finance, you’ll probably notice many recommended allocations are fairly similar. And they’re not all that tricky.

But, if you feel you could use more help, you could consider investing with a robo-advisor. This will allocate and manage your portfolio for you, typically for a relatively low fee. Alternatively, if you work with a financial planner or advisor, he or she should be able to help with an allocation too. Just make sure you aren’t overpaying for what you’re getting.

Target Date Funds and Lifecycle Funds

Another option is something called a target date or lifecycle fund. If your employer enrolls you in a default 401(k) plan, it’s possible your money will already be invested in one.

These funds are designed to automatically adjust your portfolio allocation based on your age and investment horizon. So when you’re younger and have more years to invest, they’ll put a higher proportion of your money in stocks. Over time they’ll shift more of your money into bonds.

While this style of investing can offer a convenient way to manage your portfolio, target date and lifecycle funds often charge higher fees than basic index funds. It’s important to balance the convenience with the additional cost when you’re deciding on your strategy.

Monitoring and rebalancing your portfolio

Over time, the value of your investments will change (hopefully by increasing). So you’ll want to monitor your portfolio periodically to make sure your allocation hasn’t strayed too far from your target. You don’t want to be doing this every day or week, but maybe every few months or once or twice a year.

For example, let’s say you decide to have a target allocation of 65% stocks and 35% bonds. Suppose your stocks have a great year and their value increased by 20%, but the value of your bonds stayed the same. Your portfolio would then actually be 69% stocks and 31% bonds. It would have changed simply because of the change in values.

As your allocation strays from your target, it’s a good idea to adjust your portfolio, or rebalance it, to get back to your target mix, especially if it’s become way off.

One way you could do this is to sell some of the assets you are now overweight (stocks in our example) and buy some of the assets you are underweight (bonds). But, you need to factor in the tax consequences since you’ll owe capital gains taxes when you sell investments that have gone up in value.

As an alternative approach, when you contribute more money to your investments in the future, you could simply invest more into bonds than you otherwise would. You’ll effectively be rebalancing your portfolio with the new money. Doing it this way might mean you won’t have to sell any investments that would trigger capital gains.

Sticking to your plan

Once you start investing, it can be tempting to check your portfolio every day (or even multiple times a day). But you need to be mindful of the psychological forces at hand.

When the market is charging up, it starts to feel like easy money and you’ll be tempted to buy more. And when the opposite is true, and markets are dropping, anxiety will set in, and you’ll feel pressure to sell.

Not only will this emotional roller coaster rack up trading expenses (since you pay a fee every time you buy and sell an investment), it can also cause you to buy and sell at exactly the wrong times, seriously hurting your long-term investment performance.

You don’t want to be overly active in trading your portfolio. Create a target allocation, have a plan, and stick with it.

And remember to regularly contribute more to your investments. Even if you’re starting out small, the money will add up over time.

Finally, don’t stress about having the “perfect” portfolio. There really is no such thing. There will be many potential combinations of investments that will satisfy your money needs. The important thing is to get started early, create a sensible portfolio, and build healthy investing habits that will last a lifetime.

Key Take-Aways

1) There is no perfect portfolio allocation. Many investment combinations can meet your needs.

2) When presented with multiple investment options, we tend to spread our money across them evenly (naive diversification), however, this is generally not the best strategy.

3) Determine an allocation that’s right for you, taking into account specific money needs, while paying attention to diversification and fees.

4) If you have investments in multiple places, for example, you have some in a workplace 401(k) and some in a personal brokerage account, be sure to consider them all when you think about your overall portfolio.

5) Periodically review your portfolio and rebalance if necessary.

Sign up to see the rest of this article!